World War II & Equal Rights at the University of Colorado, 1942-1945

June 24, 2016

A shorter version of this article appeared in the Summer 2016 print version of Remembrance, entitled World War II and Civil Rights in Boulder. Here is the full piece.

Introduction

The University of Colorado’s anti-discrimination effort that began in 1938 continued and gathered momentum through World War II, connecting New Deal activism with World War II idealism. As such, it provided a manifestation of a collegiate movement in Western and Northern colleges in which New Deal progressive ideology and World War II idealism were applied to attack Jim Crow both on and off campus. While this movement connected with minority students on campus and, to a much lesser degree, minority organizations off campus, such as CORE — it was mainly composed of white professors and students. Faculty, like History Chair Carl Eckhardt and the Ethnic Minorities Committee of the Faculty Senate; student groups, such as the Associated Students of the University of Colorado (ASUC), and its Ethnic Minorities Council; student groups like the Cosmopolitan Club; and white off-campus organizations, such as the YWCA, all played important roles in the struggle. Within the context of a wartime crusade, this loose, broad front against racial and ethnic discrimination was able to make considerable gains. Such was the impetus of this anti-discrimination movement that it ratified the university administration’s previous pivot from a detached stance to an active role in off-campus social problems.1

The beginning of the modern civil rights movement in the United States is often dated to Brown v. Board of Education in 1951.

The beginning of the modern civil rights movement in the United States is often dated to Brown v. Board of Education in 1951. Conditioning these arguments is the standard preference for Eastern origins and solutions to social problems, with their expected movement West. Just as influential is the judgement that the civil rights question was predominately a black-white affair, understandably defined and elaborated by its Southern expressions and battles. Settling for Brown as a start point, additionally, betrays the tendency to seek top-down causes for the movement through examinations of institutions, be they governmental or organizational. Convincing arguments have been given, recently, for somewhat earlier Western, grassroots antecedents. However, the propensity for defining and describing the campaign by only its minority-led struggles, continues from older top-down, East-West, or South centered approaches. An examination of university and faculty records of the University of Colorado reaffirms the earlier origins of the civil rights movement that only some historians have suggested. Although these records do include reports or policies from other institutions, there is no indication CU’s efforts spread from any other institution or region. Instead, the civil rights efforts at CU appear to spring from a multi-ethnic and racial grass roots impetus.2

Although the University of Colorado might not seem to have been a promising location for civil rights activism, between 1938 and 1941, liberal white students and the university faculty had already escorted the small number of somewhat reluctant black, Jewish, and Japanese-American students into beginning a crusade for equal rights by the onset of World War II.3 By 1941, the University of Colorado had already become the foci for liberal debate, unprecedented decisions, and innovative strategies. As we have seen, minorities did not need to be present in great numbers in Boulder or CU to be loathed or feared, but they also had not been required to be numerous for their rights to become a question of abiding importance. A progressive effort to alleviate discrimination on and off campus that had begun in 1938, was still attracting the attention of students and faculty during the fall of 1941, even though many of the principal student activists had already graduated. The University of Colorado provides a case of a university continuing a prewar effort on behalf of minority rights on through the years of World War II. It was a cause CU continued without consultation with other universities, perhaps because the admission of discrimination would have proved embarrassing.4

World War II Idealism & “Unrestrained Publicity”

…the onset of World War II personalized the choices among all students: between democracy and dictatorship, freedom and oppression, and racism and equality.

If international issues had provided some catalysts for liberal student activism in the 1930s, the onset of World War II personalized the choices among all students: between democracy and dictatorship, freedom and oppression, and racism and equality. The rhetoric of allied war aims legitimized liberal calls for tolerance, equality, and civil rights, magnifying and spreading the objection to segregation, while clarifying the issues involved. With the identification of democracy and equality as Allied values, totalitarianism and racism were necessarily applied to the enemy. In addition, the war itself seemed to awaken an impatient idealism in ever larger numbers of students, the Associated Students of the University of Colorado (ASUC), the Associated Women Students (AWS), and the student newspaper staff, groups that had been interested but uncommitted to the issue only three years before. As the wartime student body began to accept the torch from the prewar group, the University Administration seemed to lose the room to effectively maneuver. The quiet that had previously attended faculty-led desegregation began to give way to noisy student participation accompanied by splashes of unwelcome publicity. Moreover, on top of the problems of black students, the administration would be confronted with new predicaments involving the treatment of Japanese-American students and faculty during a war against Japan.5

Within two months of Pearl Harbor, the national rhetoric and propaganda of racial and ethnic egalitarianism had been adopted by the succeeding classes of students, students who seemed far less patient and subordinate than their predecessors. The ASUC, the clubs, and the Silver and Gold began to beat the drum for desegregation as early as February of 1942, questioning progress made to date. Within a week, the story broke suggesting that a qualified black woman had been refused acceptance to the CU Medical School. Neither the new student journalists, nor the new student and minority activists had been in on this effort as long as Professors Eckhardt and Swisher. So the students were ill informed on the real progress made since 1939, despite entertaining raised expectations about change. The members of the Faculty Senate Committee fumed. Functionally, the faculty and students were actually manifesting their different roles. Long-term faculty could afford to take the long view and conduct a drawn out siege on discrimination beyond the view of newspaper reporters. Four-year students were more likely to push for immediate results through their student newspaper. History Professor Eckhardt was especially furious, he and the Faculty Senate Minorities Committee had been conducting “a quiet campaign of education,” fully realizing that results would be slow in coming. On March 5, 1942, he scolded Stanford Calderwood, editor of the Silver and Gold and writer of the editorial that attacked faculty complacency, for having perpetrated such damaging publicity. Eckhardt challenged Calderwood and the Silver and Gold to do without the advertising from discriminatory businesses, if they were so adamant about racial injustice. Now Professor Eckhardt allowed that there were practical financial considerations. But to be consistent, Calderwood would either have to “rectify those injustices to campus minorities that are within your own jurisdiction, or take a more realistic attitude toward the solution of the far more complex general problem of minorities.” In Eckhardt’s view, the silent efforts of the committee were far more effective than “unrestrained publicity.” The faculty’s perception of the scale of the segregation problem and its dangers led them to see the matter in shades of gray; the activist and minority students saw black and white.6

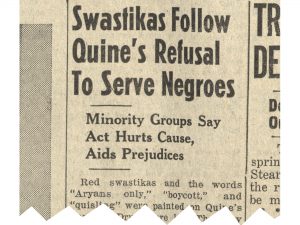

If the clash in views had continued to pit faculty against students, the desegregation campaign might have stopped dead in the water. Instead, while the faculty continued their work with the Chamber of Commerce and business owners, the students began to direct their actions against Jim Crow in Hill cafes and restaurants. In January 1943, a handful of black students began to quietly protest the Hill color bar by visiting its diners, cafes and drug stores. They quietly visited each establishment, awaiting service, armed with a copy of the anti-discrimination statute, full knowledge of University progress on civil rights, and CORE’s strategy of nonviolent protest. Quine’s drugstore vociferously refused service. That night, four white students redefined American racism as Nazism and treason by painting red swastikas, “Quisling”, “Aryans Only” and “Boycott” on the Broadway-facing wall of the drugstore. The University took a unique stance. While abhorring student vandalism, President Stearns nevertheless outlined the long and thus-far fruitless student and faculty efforts to end Hill discrimination. The hint was there for anyone to see. If you do not follow the University’s quiet lead to desegregate, the students may act to persuade you in a far less agreeable, but more public manner. The next year, the Hill color bar was finally dropped, without fanfare.7

If the racial issue at CU was not simple black and white, it was also not only about whites and blacks. President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 in February 1942 made two important contributions to the racial situation at the University of Colorado. By requiring the relocation and internment of West Coast Japanese Americans, the U.S. Navy was forced to move their Japanese Language School from Berkeley to CU. In addition, Colorado’s Japanese Americans, who had predominately attended West Coast schools were required to return to Colorado, raising CU’s Japanese American attendance from 20 in 1938 to 72 in 1945.8

Early in July of 1942 instructors arrived for the new U.S. Navy Japanese Language School. Predominately Japanese American, they arrived with their immediate families in Boulder. Many of the instructors had moved with the school from the University of California. Others were recruited from Transfer Camps or Internment Camps. Both the University administration and the cadre of the U.S. Navy Japanese Language School successfully mitigated an expected negative reaction in Boulder by meeting with the City Council, various town groups, the newspaper editor, and businessmen beforehand. They stressed the vital military nature of the school and the absolute need for Japanese instructors. In addition, uniformed students often accompanied their teachers off campus, further identifying the Japanese-American instructors with the war effort. As a result, neither Japanese-American students nor Japanese Language School instructors were confined to a ghetto. Their residences were scattered from the Hill to Downtown. The instructors were paid wages on a par with other non-Japanese, language instructors. In fact, on July 6, 1943, the instructors collectively signed a JLS faculty resolution thanking President Stearns and Captain Frank H. Roberts, USN, for their efforts on behalf of the instructors and their families.9

History professor Earl Swisher, long time member of the Faculty Senate Ethnic Minorities Committee, entered the U.S. Navy Japanese Language School as a student in July 1942, serving in the U.S. Marine Corps as a Japanese Language Officer. In 1943, Professor Eckhardt and a committee on the Institute of Asiatic Affairs began an effort, the goal of which was to ameliorate wartime animosities in the post war world. The Institute bought books, scheduled lectures, and hired teachers to acquaint the campus on the cultures and nations of the Far East. The USN Japanese/Oriental Language School cooperated with and contributed to the institute’s projects and activities. Professor Swisher brought back his wartime Japanese Language experience and took over the Institute in 1946.10

If the yearbooks of 1943 to 1945 can provide a barometer of campus life for Japanese-American students during the war, they show bleak readings. Despite increasing numbers and in stark contrast to prewar years, Nisei students were virtually absent from the class pictures and all but disappeared from the rolls of student clubs, with the increasing exception of the Cosmopolitan Club, the campus’s designated multi-racial student group. In 1943, 18 Japanese Americans made up more than a quarter of the Cosmo Club membership rolls. In 1944, 24 Japanese Americans provided more than 40 percent of Cosmo Club members. In 1945 the percentage was down to 37 percent. Moreover, of the total Japanese-American population on campus from 1942-1945, an average of one third appeared in the club yearbook photo. In the militarized campus where student portraits, fraternity composites, and group shots of clubs, honoraries, and student activities showed many in uniform, Japanese Americans were either ignored by the yearbook or chose on their own to withdraw from campus life.11

The University administration navigated a careful course between an expected anti-Japanese sentiment in Boulder and a determination not to limit Japanese-American Coloradan attendance. By establishing “quotas” for attendance, and employment, the Administration followed Army and FBI directives to appease Boulder’s wish not to accept unlimited numbers of Japanese Americans. It never seemed to matter that the total number of students never approached the imposed limit. Such legerdemain followed the established University pattern of upholding minority rights within a hostile environment. The success the University experienced with the “Japanese-American” problem mirrored its earlier progress ameliorating segregation. It had been accomplished with little publicity, in closed door meetings with city fathers, with careful consideration of which strategy would work given the off campus attitudes.12

World War II had sponsored tolerance and change. Surveys show a change in attitude that was nothing short of revolutionary.

World War II had sponsored tolerance and change. Surveys show a change in attitude that was nothing short of revolutionary. Support for desegregation had risen from a Fortune magazine estimate of 12 percent in the Midwest in 1939, to an estimated high of 97 percent among CU women in 1943. Nevertheless, the full story was far more ambiguous. Students polled in 1942 and 1943, illustrated the problem inherent in issues of race. While students unanimously supported the end of segregation in honoraries and associations and a large majority supported and end to “white-only” cafes and barbershops, ever smaller majorities agreed they would share housing, socialize, or room with Black or Japanese students. Most admitted they would not want to room with a Black student. So while editorialists, student commissions, and the ASUC attacked discrimination, there were clearly limits to what students, their parents and the faculty could accept. In March, a poll of sorority and independent women revealed similar findings. Eighty-eight percent and 97 percent, respectively, objected to the color bar in Hill restaurants, 75 percent were against segregation in theaters and meetings. Just 75 percent would have sodas with Japanese, only 40 percent with blacks. Almost no women would room with a minority. These findings reflected the 43 percent of CU who agreed to fill out the questionnaire, which may have included the liberal side of the student body. If so, the limits of tolerance were clearly defined. Nevertheless, such a high percentage of opposition, if only for the idea of segregation, demonstrated an immense shift in opinion regarding racial separation.13

On October 3, 1945, Dr. Eckhardt wrote President Stearns that he was justifiably pleased with the work of the Faculty Senate Committee on Minorities. By the standards of the problem set out in 1938, the work of the committee had been completed. So successful had the committee been that Eckhardt had been forced to have multiple copies made of his committee report. Other colleges and universities had bombarded CU with requests for information regarding their experiences with minority problems. Moreover, it appears that what had occurred at CU had also happened at a number of other universities. Eckhardt agreed that “on the surface it looks as though the Senate committee has completed its services, but it is my opinion that in case future emergencies arise it would be well to have a Senate committee in existence to handle the situation.” Professor C.C. Eckardt retired that year from the University and died in 1946. President Stearns accepted Eckhardt’s advice and continued the committee’s mandate, for emergencies did arise.14

Conclusion

Robert Cohen cites Depression-era student activism against racial discrimination as marking “an important turning point in the history of collegiate racism.” While he did not extend his study of university protest into World War II, he nevertheless asserted that 1930s campus organizers initiated a campaign that would later become the full-scale assault on both racism and segregation. Events at the University of Colorado both support and augment Cohen’s analysis of “America’s first mass student movement.”15 At the University of Colorado, however, the administration, faculty, and students were not necessarily arrayed against each other. Minorities, few in number, did not find the overwhelming white populace staunchly committed to the continuance of Jim Crow. Town and gown were not intractable enemies, either. Much of the difference between Cohen’s description and the CU experience can be attributed to the fact that none of the original faculty committee could have been accused of being part of the “Left”. No, Eckhardt, Stearns and Swisher were decidedly “Center.” Perhaps it is due to their “centrism” that student, faculty, minority, and community participants in the University of Colorado’s civil rights effort were able to combine in a loose coalition to promote successful outcomes. Nor were CU’s endeavors for student equality confined to the Depression. Clarion calls for fairness and justice had been sounded earlier, were acted upon during the 1930s, and carried through more successfully later, during World War II.

During the Depression, domestic troubles, international crises, and the start of a world war in 1939 elicited an increasingly liberal reaction from the independent portion of the student body, or Barbs (barbarians as opposed to Greeks). A vibrant peace movement, a willingness to experiment with a wide variety of political credos, and a commitment to a range of social causes seemed to have engaged a considerable number of influential white students. Honors students, officers and members of a wide variety of social clubs and honoraries, editors and writers for the Silver and Gold, combined with members of the American Student Union and the Cosmopolitan Club to “light a fire under” the ASUC on the matter of civil rights. Although an admittedly short list, the minority student rolls contributed keenly focused and energetic black, Japanese-American, and Jewish spokespeople on matters of racial and ethnic equality. As the movement progressed they became less watchful and more demanding of their equal treatment. However, activists and professors alone could not have moved the students, faculty, regents, and townspeople toward tolerance had not that same majority finally become accomplices themselves. Faculty and student efforts were swept along by a world war cast as a democratic struggle against fascism and racial hatred, an imperative around which coalesced a consensus on behalf of equality. The merging of activism and wartime idealism carried out nothing short of a revolution in civil rights at the University of Colorado.

The first move had been made. But it was only a first move. Neither long-held public and campus opinion nor the traditional practice of many decades could be changed completely in six years. The first phase of desegregation forced mere access. However, access would often take the appearance of segregation within the institution so opened. The Boulder Sanitarium promised to take African-American students whom it would house and feed separate from the rest of their patients. CU residence halls accepted black applicants but found they needed to assign them their own rooms as officials worried that white students might refuse to share bathrooms with black students. African Americans were accepted into the CU Medical School, but were forced to tolerate the racist assumptions and behavior of professors, patients, and fellow students alike. Minority students unwelcome at Hill restaurants were to find food and refreshments at the new student coop in the Memorial Building, but interracial mixing caused trouble. Japanese-American students were allowed to enter the University in unprecedented numbers during the War, but their social lives seemed confined to the Cosmopolitan Club or Japanese-only activities for the duration. The mechanisms of student government had begun to end the practice of ethnic and racial exclusion in honoraries and student clubs, but the effort had only begun a process that would take many years to finish. Hill restaurants grudgingly opened their doors to black students in 1944, but at least one restaurant, the Sunken Gardens, would try to put all African-American patrons at one table. In any case, black students knew the difference between open doors and open minds and did not frequently test their welcome in Hill establishments. Historian C.C. Eckhardt’s “quiet campaign of education” on civil rights had ended, but Boulder and the University of Colorado were a long way from “graduation.”16

- David M. Hays, “‘A Quiet Campaign of Education’: Equal Rights at the University of Colorado, 1930-1941,” in Arturo J. Aldama, with Elisa Facio, Daryl Maeda, and Reiland Rabaka, eds., Enduring Legacies: Ethnic Histories and Cultures of Colorado (Niwot, CO: University Press of Colorado, 2011), 159-174. ↩

- see Adam Fairclough, “Historians and the Civil Rights Movement,” Journal of American Studies, 24, No. 3 (1990): 387-398; Steven F. Lawson, “Freedom Then, Freedom Now: The Historiography of the Civil Rights Movement,” American Historical Review, 96, No. 2 (1991): 456-471; Quintard Taylor, In Search of the Racial Frontier: African Americans in the American West, 1528-1990 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1998), 278-310. ↩

- For an overview of minorities in the Denver area, see Robert M. Tank, “Mobility and Occupational Structure on the Late Nineteenth-Century Urban Frontier: the Case of Denver, Colorado,” Pacific Historical Review 47, No. 2 (1978): 189-216; Robert L. Brunton, “The Negroes of Boulder, Colorado, A Community Analysis of an Ethnic Minority Group,” M.A. thes., University of Colorado, 1948; James A. Atkins, Human Relations in Colorado, 1858-1959 (Denver: Colorado Department of Education, 1961); Ira De A. Reid, “The Negro Population of Denver, Colorado: A Survey of its Economic and Social Status,” New York: National Urban league, 1929; for general ideologies at universities, see Allan Nevins, The State Universities and Democracy (Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 1962); Calvin B.T. Lee, The Campus Scene, 1900-1970: Changing Styles in Undergraduate Life (New York: David McKay Company, Inc., 1970), 1-87; and Clyde W. Barrow, Universities and the Capitalist State: Corporate Liberalism and the Reconstruction of American Higher Education, 1894-1928 (Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Press, 1990), 186-220. ↩

- For a discussion of racism without minorities, see David R. Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class (New York: Verso, 1991), 3-5; for early campus activism, see Eileen Eagan, Class, Culture, and the Classroom: the Student Peace Movement of the 1930s (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1981) and Robert Paul Cohen, When the Old Left was Young: Student Radicals and America’s First Mass Student Movement, 1929-1941 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993); for a discussion placing the onset of the modern civil rights movement in the 1930s and World War II, see Harvard Sitkoff, A New Deal for Blacks: The Emergence of Civil Rights as a National Issue, Volume I: The Depression Decade (New York, Oxford University Press, 1978); Merl E. Reed, Seedtime for the Modern Civil Rights Movement: The President’s Committee on Fair Employment Practice, 1941-1946 (Baton Rouge, La.: Louisiana State University Press, 1991); see also Stephen F. Lawson, Running for Freedom: Civil Rights and Black Politics in America Since 1941 (New York: The McGraw-Hill Cos., Inc., 1997), especially p. 1-28 and his bibliographic essay, 290-291; for a grassroots look, see Michael K. Honey, Southern Labor and Black Civil Rights: Organizing Memphis Workers (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993). ↩

- For the linkage between World War II and egalitarian ideals, see Peter J. Kellogg, “Civil Rights Consciousness in the 1940s,” Historian, 42 (November, 1972): 18-41; Pollenberg, 46-85; for local writings, see Ralph Crosman, “Crisis Confronts CU, Professor Crosman Tells Alumni,” The Colorado Alumnus, 29, No. 1 (October, 1938): 7 and Colin Goodykoontz, “Jeffersonianism in 1943,” Colorado Alumnus, 34, No. 3, (October, 1943): 6-8; For a student editorial connecting war aims with a civil rights message, see “We’ll Never Lynch Hitler this Way,” Silver and Gold, January 27, 1942, 2. ↩

- William Rentfro, “Without Drums,” Silver and Gold, Feb. 16, 1942, 3; “CU Negro Advised Against Medical School,” and William Rentfro, “Without Drums,” Silver and Gold, Feb. 24, 1942, 1,2; “No Race Discrimination Here, Say Faculty” and “Why are Vested Faculty Interests so Anxious to ‘Disprove’ Stated Facts?” Silver and Gold, Feb. 27, 1942, 1,2; “CU Committee Denies Implication of Discrimination against Negro,” Boulder Daily Camera, Feb. 25, 1942, 1,6; see also February, 1942 correspondence between NAACP, the Denver YWCA, and the Denver Interracial Commission and Robert L. Stearns, President’s Office Papers, I-56-1, Archives, University of Colorado Boulder Libraries (AUCBL); “Backing Given to Hopes of Search into Racial Issue,” and William Rentfro, “Without Drums,” Silver and Gold, March 3, 1942, 1,2; C.C. Eckhardt to Stanford Calderwood, March 5, 1942, C.C. Eckhardt Collection, 1-16, AUCBL. ↩

- “1 Restaurateur Attends Confab,” Silver and Gold, December 4, 1942, 1; “Four Colored CU Students Refused Cokes in Quines,” Silver and Gold, Jan. 29, 1943, 1; Inspired by CORE’s theory on nonviolent protest, Harry Groves, Dolores Hale and Mabel Wheeler also performed “sit ins” at theaters in Boulder and at restaurants in Denver accompanied by members of the YWCA, see Harry E. Groves to David M. Hays, June 2, 1998 and Telephone Interview with Mabel Wheeler, July 9, 1998; see public message, Jan. 29, 1943, President’s Office Papers, I-56-1, AUCBL; “Swastikas Follow Quine’s Refusal to Serve Negroes,” Silver and Gold, Feb. 2, 1943, 1; “Swastikas on Drug Store are Probed,” Boulder Daily Camera, Jan. 29, 1943, 1,8; Harry Carlson to President Stearns, Feb. 11, 1943, President’s Office Papers, I-56-1, ACUBL; “Students Confess Defacement of Quine’s Drug Store,” Boulder Daily Camera, Feb. 16, 1943, 1; Nona Neithammer, “Negro Students Now Welcome at Hill Food Spots,” April 16, 1943, 1; C.C. Eckhardt to Robert Stearns, Oct. 3, 1945, C.C. Eckhardt Papers, 1-16, AUCBL; curiously, at no time during this period did the Boulder City Attorney, the Boulder City Council or the Police Force ever attempt to enforce the anti-discrimination law already in the books. ↩

- David M. Hays, “No Invisible Minority: Japanese Americans at the University of Colorado, 1910-1945”; see Donald Paul Irish, “The Reactions of Residents of Boulder, Colorado to the Introduction of Japanese into the Community,” M.A. Thesis, University of Colorado, 1950, Appendix II, 173; Colorado University Student Directory, 1938-39-1943; Colorado University Student Directory, 1944-1948; For more on Japanese Americans on college campuses during World War II, see Thomas James, “‘Life Begins with Freedom’: The College Nisei, 1942-1945,” History of Education Quarterly, 25, Nos. 1-2 (1985): 155-74; Gary Y. Okihiro, Storied Lives: Japanese American Students and World War II, (Seattle : University of Washington Press, c1999); see the page 2 editorials in the Silver and Gold, April 27, April 30, May 7, May 18, 1943. ↩

- see Irish, 20-44; Roger Pineau Collection, 18-22, AUCBL; Regents Minutes, Jan. 16, 1942-Dec. 17, 1943, p. 214 and Exhibit G; Silver and Gold, June 18, 1942, 3; June 25, 1942, 2,4, Nov. 6, 1942, 5; Nov. 20, 1942, 1; Jan. 8, 1943, p. 1 (2 stories); Jan. 19, 1943, 1,3,5; Jan. 22, 1943, 1; June 30, 1943, 2,4,5; July 7, 1943, 2; July 13, 1943, 2; July 16, 1943, 2; “City, CU Agree on Restrictions of Japanese Aliens,” Boulder Daily Camera, Jan. 20, 1943, 1; it is possible that a large portion of these Colorado resident students were the college-age children of West Coast Japanese American migrants who had fled California before the internment. ↩

- “C.C. Eckhardt, “The Institute of Asiatic Affairs of the University of Colorado,” The Colorado Alumnus, v.35, n.3 (September 1944) 1; Major Earl Swisher, “Formosa, Land of Strange Customs … With that Certain Fascination,” The Colorado Alumnus, v.36, n. 12 (June 1946) 3-4. ↩

- for the concentration of Japanese Americans in the Cosmo Club, along with their disappearance from other activities, see the Coloradan, 1943, 1944, 1945. ↩

- Board of Regents’ Minutes, January 1942-December 17, 1943, p. 32-33,54,72,73, AUCBL; “CU to Admit Japanese from Coast Colleges,” Boulder Daily Camera, March 25, 1942, 1; W.F. Dyde to Robert L. Stearns, July 23, 1942, Robert L. Stearns Collection, 21-1, AUCBL; Board of Regents’ Minutes, Jan. 2, 1944-Dec. 27, 1945, p. 17, Exhibit D, Memorandum to President Gustavson, Feb. 7, 1944, p. 72, Exhibit F, Rex A. Ramsey to R.G. Gustavson, July 11, 1944, AUCBL; Boulder City Council Minutes, July 1944, Carnegie Branch, Boulder Public Library. ↩

- “Women Oppose Exclusion of Racial Groups from Cafes,” Silver and Gold, Jan. 6, 1943; Gene Perkins, “Sorority Girls and Independents Favor Democratic Restaurants,” Silver and Gold, March 5, 1943, 1-2. ↩

- Ibid.; In early 1946, the University of Wisconsin student body social relations committee conducted a survey of 67 major universities on matters of discrimination and found 50 percent to have active programs to diminish prejudice and discrimination, “Race Discrimination Survey Conducted by U. of Wisconsin,” Silver and Gold, June 18, 1946, 3; Meier and Rudwick made several observations about the participation of college students in the founding decade of the Congress of Racial Equality, stating that 26 of the 39 identifiable charter members were white college students and estimating between 30 percent to 50 percent of CORE affiliates were college groups, suggestive of the presence of civil rights activism in a number of universities during World War II, see August Meier and Elliott Rudwick, CORE: A Study in the Civil Rights Movement, 1942-1968 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973), 8, 23, and 24. ↩

- Cohen, 225 ↩

- C.C. Eckhardt to Robert L. Stearns, Oct. 3, 1945, C.C. Eckhardt Collection, 1-16, AUCBL; C.C. Eckhardt to Mrs. Jerome C. Smiley, May 1, 1944, C.C. Eckhardt Collection, 1-16, AUCBL. ↩